When Small Models Are Good Enough: A Peek into Geometry of Intelligence

TL;DR

Most everyday prompts are reshaping meaning that’s already there, not creating new concepts (local manifold walks - explained below). Small models handle this fairly competently, and will help you save on costs and resources. Big models matter when you need global consistency across multiple reasoning hops.

I routinely burn Claude Opus tokens to fix typos. I’ve used Sonnet to reformat markdown. Last week I spent $12 having GPT-4 summarize a transcript I could have skimmed in three minutes.

It’s like doing long division with a supercomputer.

I’ve written before about hitting Claude Code’s token wall almost every session. To stay under rate limits-and stop lighting money on fire-I need a routing framework based on what the task actually requires, not what I habitually reach for.

The Geometry: Reshaping vs. Creating

Here’s the mental model that finally made this click for me.

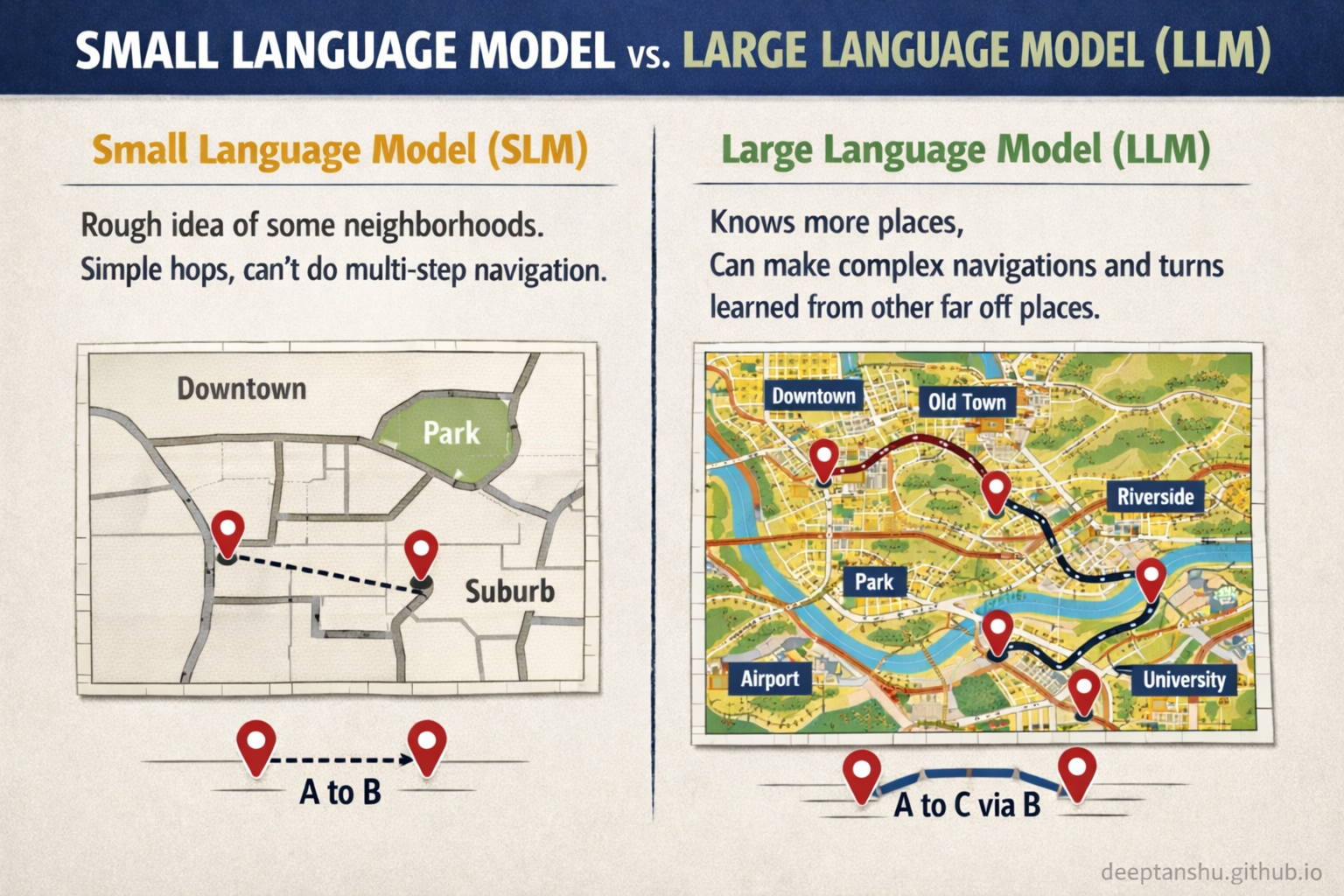

Imagine all possible human thoughts as a vast topographic map. Large models can traverse the entire map, connecting distant continents of meaning. Small models are specialists in the local neighborhood. They don’t explore far. They rearrange what’s nearby.

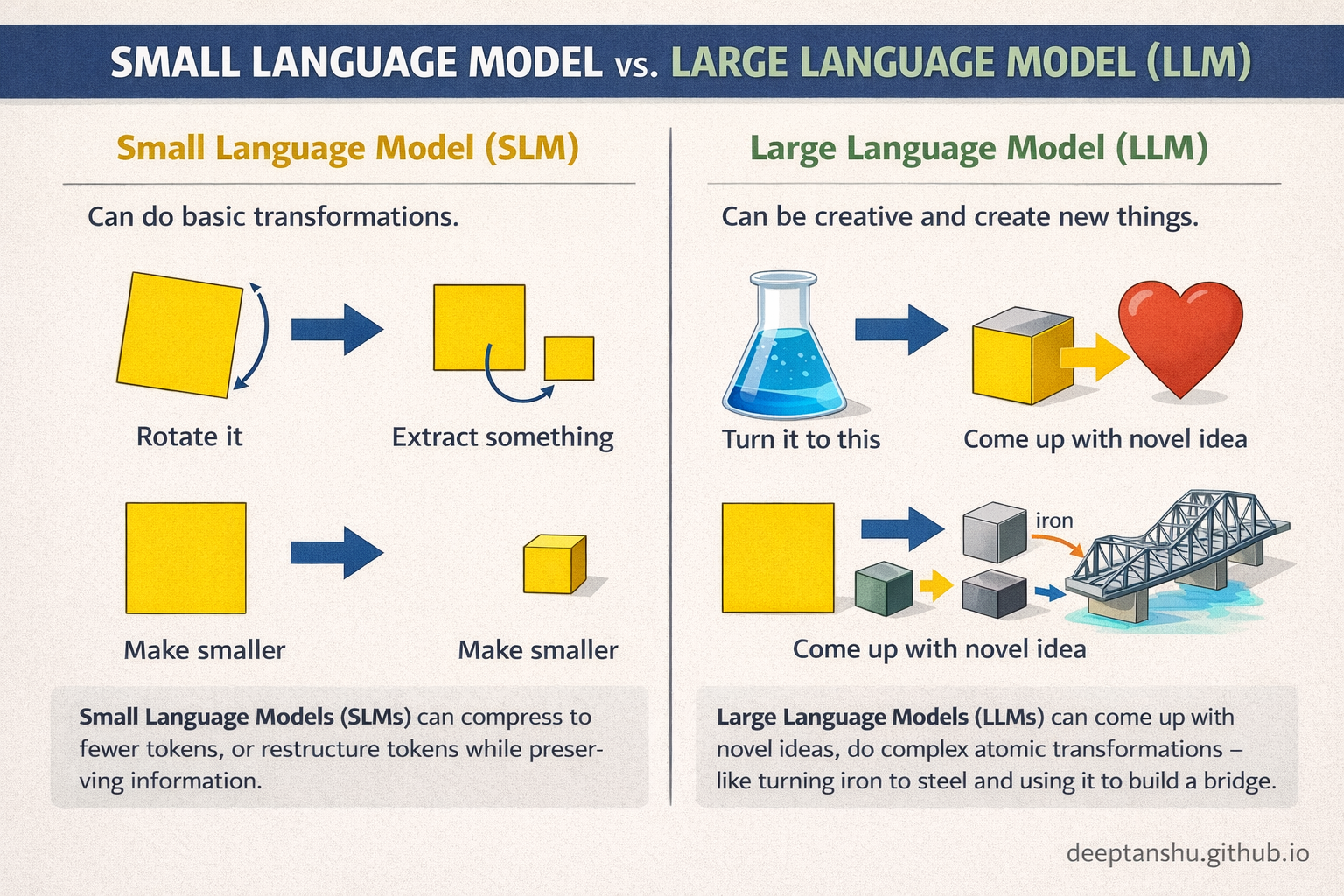

This matters because most “daily-driver” prompts aren’t asking a model to discover anything. I’m asking it to take existing information and reshape it: summarize this, make it sound professional, extract the action items. These aren’t creative tasks. They’re geometric tasks.

The three I use most: restructuring (pull out the important parts), rewriting (change the tone or tighten the language), and extraction (find the decisions or risks buried in here). None of these require a model to invent concepts. They require it to recognize patterns and rearrange tokens.

Why Small Models Can Do This

At the transformer level, your input tokens already live in semantic clusters. Sentences about the same topic are already neighbors in vector space.

Restructuring is about reweighting attention-figuring out which vectors matter most-and then suppressing redundancy. The model drops low-salience tokens and re-emits the high-salience ones in a cleaner sequence. This is cheap in terms of model capacity because no new concepts are required. The model is a filter, not a factory.

Rewriting is a local manifold walk. When I ask a model to “make this sound more professional,” I’m not asking it to jump to a new continent of meaning. I’m asking it to move slightly to the left. The original sentence and the rewritten one occupy the same semantic basin. In vector terms, vec(v)_input ≈ vec(v)_output. Because the embeddings are already close, the model doesn’t need to invent anything. It projects the existing idea onto a different stylistic surface.

This is why small models handle tone shifts, grammar fixes, and tightening language so well. They’re interpolating, not discovering.

Extraction works because these are classification tasks disguised as generation tasks. The model already knows the shape of an action item, a decision, an assumption. It scans the prompt until a span of tokens snaps into that latent pattern. Like a magnet snapping onto metal filings already scattered on the table. Pattern recognition, not global planning.

Why This Maps to Model Size

The reason this works comes down to dimensionality and depth.

Dimensionality is how big the map is. A small model typically has a d_model of around 768 to 2,048. In this space, “Apple” the fruit and “Apple” the company are distinct, but fine-grained distinctions get crowded. Context resolves ambiguity, but there’s limited room for nuance.

A large model typically has a d_model of 4,096 to 12,288 or higher. With more dimensions, the model can untangle concepts cleanly. It can separate physical properties, financial abstractions, cultural symbolism, and historical context without them interfering with each other. More dimensions mean more conceptual elbow room.

Layers are what move you across the map. A small model has fewer layers-maybe 12 to 24. That means it can only apply a small number of transformations before it has to answer. This makes it great at interpolation, finding a short path between nearby points: casual tone to professional tone. Fast, cheap, reliable.

A large model has many more layers-80, 100, sometimes more. Each layer is another opportunity to abstract, compress, reinterpret. This is what allows a large model to connect ideas that start far apart and meet only after dozens of transformations. This is why they can do zero-shot reasoning and multi-hop synthesis. They have the lanes to cross continents.

The Residual Stream

If layers are the steps across the map, the residual stream is the highway system that keeps you oriented.

Think of it as a continuously flowing notebook that every layer can read from, write to, and refine without erasing. It prevents catastrophic forgetting. Early signals don’t disappear; they accumulate. For small models, this means the original intent stays intact during local edits. For large models, this means long chains of reasoning can remain coherent over dozens of transformations. Without the residual stream, deep reasoning collapses into noise.

When Small Models Fail (and I Learn the Hard Way)

Small models break when the geometry of the task requires global consistency.

Last month I tried using Llama 3.1 8B to refactor a 400-line Python module. The first 50 lines looked great. By line 200, variable names were drifting. By line 300, it had forgotten the original architecture. By line 400, nothing compiled.

Deep reasoning requires maintaining multiple latent variables across time. If a task requires 10 steps of logic, and each step has a small chance of drifting off-manifold, a small model will be nowhere near the truth by the end.

I route to a big model when the abstraction depth is high-multiple hops of logic, synthesis across distant concepts, or when global state must remain consistent over time. Large refactors, long proofs, system design. Anything where losing the thread halfway through means the output is worthless.

The Routing Heuristic I Actually Use

Before I hit Enter on a massive context-window prompt, I run this heuristic:

Difficulty ≈ Delta Information + Global Dependency Depth

If I’m reshaping information that already exists in the prompt-summarizing, reformatting, extracting-I use a small model. If I’m asking the model to create new abstractions or maintain consistency across dozens of reasoning steps, I use a big model.

I’m still bad at this. I still default to Opus for tasks that Haiku could handle. But I’m getting better. The geometry metaphor helps. Restructuring is local. Creation is global. Route accordingly.

Save your intelligence budget for tasks that require creation, not rearrangement.